Scientists tracking warm water reminiscent of the “Blob” in Northeast Pacific

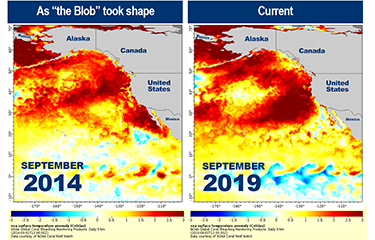

Scientists are tracking a marine heat wave reminiscent of the one that formed in the northeast Pacific from 2014 to 2016, memorably dubbed the Blob.

Cisco Werner, the chief science advisor for the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration’s fisheries division, warned of the heat wave at a conference on the ocean’s role in sustainable food supply which took place on 16 September at the University of California, Davis.

“The first heat wave, nobody even knew what it was when it happened. And we learned a great deal,” Werner said during his keynote address at the conference. “We’re watching this one very closely, this one that’s happening now.”

In his keynote, Werner also gave a broad overview of the state of fisheries around the world, and the upcoming trends that the seafood industry will confront in the coming years.

The long-term trend of warmer ocean waters caused by climate change is already causing the migration of fish stocks, such as black sea bass, which have migrated north along the U.S. East Coast, Werner said. In Alaska’s Bering Sea, lack of sea ice and changes in ocean productivity are changing the distribution of Pacific cod.

Climate change is having a profound effect on the foundation of the marine food chain. Werner noted that warm waters in the northeast Pacific have driven a change in lipid-rich zooplankton to another kind of zooplankton that is lipid-poor — and this, essentially, results in less energy in the food web.

The recurring heat waves could be attributed to higher baseline temperature, or they could be attributed to greater variability in ocean temperatures, Werner said. Regardless, they’re happening, and fishermen are being affected.

“They’re happening more frequently. They’re happening more often. The question is how do we forecast them?” Werner said. “How do you incorporate this into stock assessments? How do you bring this into ecosystem considerations of the wild capture fisheries?”

The seafood industry is already being impacted by the warmer waters. “This is taking a toll pretty quickly,” Werner said. The seafood industry must make decisions such as investments in processing capacity and ships – and those decisions will be influenced by ocean conditions such as the heat waves.

“I’m leaning toward thinking these weren’t isolated events,” Werner said. “We’re looking toward a different kind of regime, system, than we’re used to looking at.”

This current heat wave appears to be the second largest heat wave in geographic area, after the Blob, according to Andrew Leising, a research scientist at NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center in La Jolla, Calif.

The Blob’s warm temperatures peaked in 2014 and 2015 at close to 7 degrees Fahrenheit (about 3.8 degrees C) above average, and resulted in the largest harmful algal bloom on record on the West Coast, which shut down crabbing and clamming. It also drove multiple fisheries to be declared disasters.

The current heat wave does not extend as deep into the water column – just the upper 20 meters, compared to the top 120 meters that were warm during the Blob event, Leising told SeafoodSource.

“This is important because it means that this current marine heat wave could dissipate more rapidly if atmospheric conditions change, and thus we would not have as large effects as last time,” Leising said. “I would not advise (fishermen) to worry yet, but they should be aware that there is a marine heat wave happening.”

Different regions of the Pacific are likely to see different impacts, according to Nick Bond, an associate professor at the University of Washington, and the Washington State Climatologist, who is credited with naming “the Blob.”

“We are seeing some impacts on Pacific cod in the Gulf of Alaska, and on a persistent harmful algal bloom in Puget Sound,” Bond told SeafoodSource. “It remains to be seen how all of the impacts on the marine ecosystem play out.”

Fall storms are likely to push temperatures back closer to normal in the Pacific Northwest, where the warm water doesn’t go as deep. But in the northern Gulf of Alaska, where the water extends to greater depths, the impacts may be greater, Bond said.

“It is rather disturbing that we are having this conversation so soon on the heels of the very severe marine heat wave for 2014-16,” Bond said.

Image courtesy of NOAA

Share