Hawaii marine monument expansion’s impact on fishing debated 5 years later

Tensions flared fast as the proposed expansions of national marine monuments near Hawaii in President Barack Obama’s second term set fishermen and conservationists against each other.

The Hawaii Longline Association, representing about 150 permitted vessels, objected to fishermen being locked out of fishing grounds. Conservationists aligned with The Pew Charitable Trusts, which advocates for marine protected areas (MPAs) around the world, and rallied for the preservation of coral reefs, unknown life in the deep sea, and the area’s natural and cultural resources.

The financial effects on fishermen — and whether the conservation gains were worth the cost — are still being debated today, with recent research offering conflicting answers. It’s a lingering question for fishermen now struggling with new financial disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

With two strokes of a pen, Obama expanded first one marine monument then a second in 2014 and 2016, collectively protecting more than one million square miles. The expansions contributed to the displacement of Hawaii-based fishermen from U.S. waters onto the high seas, where they face stiff competition from foreign vessels, according to Hawaii Longline Association Executive Director Eric Kingma.

About 65 percent of the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) around Hawaii is now closed to the fleet, Kingma said. Add in the Southern Exclusion Zone, and only 17 percent of EEZ waters around Hawaii are open to fishing.

"About 90 percent of our effort is now on the high seas," Kingma told SeafoodSource. "It's antithetical to what we're trying to do here with having a highly-monitored, sustainable fishery.”

Since President Theodore Roosevelt signed the American Antiquities Act into law in 1906, presidents have burnished their legacies by cordoning off areas of unique historic or scientific interest.

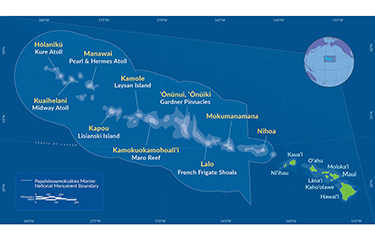

In 2006, President George W. Bush created the first ocean-based national monument by designating the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument, which was soon renamed Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. In 2009, Bush designated the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.

Obama expanded first the Pacific Remote Islands, then Papahānaumokuākea, in 2014 and 2016. Today, the two monuments are the third- and fifth-largest protected areas in the world, and encompass an area larger than the landmass of Argentina.

Such presidential declarations are a far cry from the participatory, stakeholder-driven process U.S. fishermen are accustomed to with the U.S. Regional Fishery Management Councils or even the international regional fishery management organizations — a fact that irks fishermen.

The Hawaii-based longline fishing industry is the most lucrative in the region by far. Nearly all of the 150 permitted vessels are based in Honolulu, and most target bigeye tuna with deep-set gear. About 15 of the vessels also seasonally target swordfish with shallow-set gear.

Half a decade after the Hawaii monument expansions, the longline association insists that fishermen locked out of their former fishing grounds have suffered, even as emerging research arrives at differing conclusions about the monuments’ economic impact on the fleet.

"Fishermen know that you've got to be able to have access to fishing grounds when the fish are there, especially with tuna and highly migratory species," Kingma said.

Kingma argues that the main purpose of the monuments was to protect the seabed, especially sensitive corals, from mining or possibly bottom-trawling. Longliners fish only in the upper 1,000 feet of the water column, leaving the vast depths untouched.

"There could have been an exemption for our fleet because it's highly monitored. We know everything we catch, and it's highly traced and documented," Kingma said.

To be sure, benefiting fishermen and their pocketbooks isn’t really the purpose of MPAs, many of which aren’t created with economic benefits or drawbacks in mind.

"It also depends on what you're looking for. There were some areas that were set up not for economic reasons," Matt Rand, who directs the Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy Project, told SeafoodSource. "Papahānaumokuākea was as much about protecting culture and traditional connection to a place as it was for economic reasons. The focus really was not to drive economic reasons."

One recent study, published by University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Professor John Lynham, and funded by the Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy Project, concluded that the negative effects of the monument expansions were minimal.

Post-expansion, the fleet is catching more fish while traveling the same distance to do so. Average revenue was 13.7 percent higher from 2014 to 2017 than it was from 2010 to 2013. Total catch and total revenue increased.

"The data is suggesting so far that the industry seems to be catching just as much as before, and there doesn't seem to be evidence that they're exerting more effort to get that catch," Lynham told SeafoodSource.

In his study, Lynham used a comparative analysis method common in medical research and economics, but rarely applied to fishery research. Researchers struggle to pinpoint specific cause-and-effect relationships in fisheries because catch and revenue are affected by so many intersecting conditions: regulations, prices, ocean conditions, and competition.

So rather than directly comparing the fleet’s catch and revenue before and after the expansion, Lynham identified separate control groups. The study narrowed in on the specific effects of the national monuments by comparing the longline tuna fishery to two other fisheries unaffected by the monument designations, yet subject to the same management rules and oceanographic conditions.

He compared the Papahānaumokuākea expansion to the American Samoa longline albacore tuna fishery, and the Pacific Remote Islands expansion to the Hawaii longline swordfish fishery, which also catches bigeye and yellowfin tuna incidentally.

Lynham found that the monument expansions did not cause fishermen to suffer — a result that wasn’t surprising, given the fact that in 2015, when Papahānaumokuākea was still open to fishing, 97 percent of fishing was in areas outside the expansion waters.

"The big reason for why that's the case compared to other protected areas in other places with larger impacts is because the reality is they just weren't doing that much fishing in the expansion area prior to the monuments," Lynham said. "There wasn't a single year where even 10 percent of sets or catch was coming from that area. If you can still go to 90 percent of your fishing areas, then maybe it's not surprising that catch and revenue and catch per unit effort haven't gone down.”

Future benefits to fishermen might also be possible. Part of the Pacific Remote Islands monument protects spawning grounds for bigeye tuna, but it’s too early to test, Lynham said.

A separate study reached a different conclusion on the effect of just the Papahānaumokuākea expansion, finding that the subset of fishermen who used the monument expansion area more heavily prior to the closure were negatively affected.

After the monument expansion, catch per unit effort fell 7 percent, revenue per trip dropped 9 percent, and vessels lost out on USD 3.5 million (EUR 3.2 million) of revenue in the first 16 months post-expansion, according to study author Hing Ling Chan, a senior fisheries economic project manager with the University of Hawaiʻi’s Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research. Chan is also affiliated with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center.

The affected vessels were those that Chan classified as high-effort — 6 percent or more of their total effort was inside the monument expansion area. A total of 37 vessels fell into that category, or less than one-third of the vessels that qualified.

"Fishermen are likely still in the process of becoming more efficient in finding areas with comparable productivity relative to those found in their traditional fishing grounds," Chan told SeafoodSource. "In the longer-term, when longline fishers find productive fishing areas outside the monument, they will likely become more efficient and the negative economic impacts have the potential to decline."

The two conflicting studies reflect a research field that is still in flux, especially since evaluating the economic effect of an action is a tricky proposition. Analyses of the benefits and drawbacks of MPAs are still evolving — and rare because they’re tough to do, according to Dalhousie University Postdoctoral Fellow Kristina Boerder, who studies the interaction of fisheries and large-scale MPAs.

"It tends to be sometimes a bit of a trench war between conservationists and the fishing industry, and neither side really wants to soften their position," Boerder told SeafoodSource. "Increasing fish catch is not one of the main aims of a protected area, but it's a nice benefit and it certainly helps ease resistance from the fishing sector.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia

Share