Genetic studies confirm Alaska cod stocks pushing north

Biologists were shocked in 2017 when they found that the numbers of Pacific cod had risen exponentially in the northern Bering Sea off the coast of Alaska. Now, researchers at NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center have used genetic testing to prove that those fish, enabled by warming waters and a lack of sea ice, have moved north from the southeastern Bering Sea.

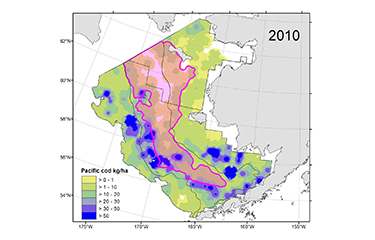

Surveys as recent as the 1970’s revealed “trace amounts” of cod in the northern Bering Sea, according to a brief released by NOAA. Major Alaska cod fisheries in the past decades have operated in the southeastern Bering Sea, the Aleutian Islands, and the Gulf of Alaska, which meant management biologists conducted only sporadic bottom trawl surveys in the north.

In 2010, an Alaska Fisheries Science Center survey found an estimated 3 percent of the massive southeastern Bering Sea stock in northern waters. Seven years passed before the next northern survey, and this time the findings were shocking: cod abundances in the north had shot up 900 times from 2010. The wild swing prompted NOAA to run another bottom trawl survey the following year, and in 2018, the biomass in the north overcame the biomass in the southeast.

Ingrid Spies, a Science Center biologist, led the study to figure out where the Pacific cod in the north were coming from.

“It could have been the expansion of a small existing population in the northern sea. It could have been fish moving in from Russia, or from somewhere else in their known range; maybe it was the missing Gulf of Alaska cod whose numbers declined significantly in 2017,” Spies said in the report.

With help from University of Washington researchers, Spies ran genetics on the fish and found them to be genetically identical to the cod population found in the southeastern Bering Sea.

“That meant the fish were moving north from their historical southeastern Bering Sea habitat. We could rule out the other possible origins for the fish sampled,” Spies said.

The push north, biologists believe, has been facilitated by warming waters and a lack of winter sea ice that forms the cold pool, a finger of water below 2 degrees Celsius that is left at the bottom of the eastern Bering Sea when ice retreats. Pacific cod, along with walleye pollock and several species of flatfish, avoid the cold pool, and it serves as a kind of migratory guide, steering cod back south.

Spies and her team are still unsure whether the cod population has shifted their spawning grounds to the northern Bering Sea or are just embarking on longer feeding migrations, but biomass relocation could have enormous consequences for the fishing industry. Pacific cod numbers have imploded in the Gulf of Alaska in the past years, and the total allowable catch has dropped incrementally in the southeast Bering Sea as well. Trawling is not currently allowed in the northern Bering Sea, which may set up a management showdown.

Meanwhile, Spies said NOAA biologists will be keeping a far closer eye on the Bering Sea, and not just for cod.

“This emphasizes the need for continued northern and southeastern Bering Sea surveys and for tagging studies. This is probably not the only species we will see changing. We really need to monitor the northern Bering Sea with surveys every single year until things stabilize,” said Spies.

Photo courtesy of the NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center

Share