Ecuador’s tilapia export market unlikely to recover to prior heights

Say the words “Ecuador” and “seafood” and one concept will invariably come to mind: shrimp, and for good reason.

The South American country has seen extraordinary growth of its exports of the crustacean, moving more than USD 3.6 billion (EUR 3 billion) and with market players diversifying in different geographies and market sectors. But just over a decade ago, shrimp was not the only seafood product with a promising future; the export of tilapia to the U.S. was a burgeoning market.

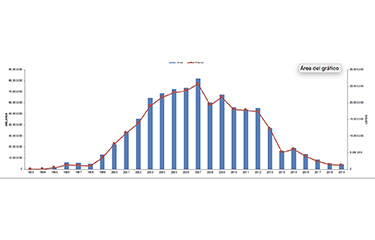

Reviewing statistics from Ecuador’s Camara Nacional de Acuacultura (CNA), one can observe steady growth of tilapia exports from 1999 through 2007, a year in which the market peaked exporting nearly 30 million pounds (13,608 metric tons) and earning close to USD 80 million (EUR 68 million). However, since 2007, the market has steadily declined, reaching insignificant figures today. SeafoodSource spoke with CNA’s Executive President, José Antonio Camposano, to learn how the market shifted, and why.

SeafoodSource: There were significant increases in tilapia exports until 2007, when you exported tilapia worth USD 80 million (EUR 68 million), but from there you see a significant, continual decrease. What happened?

Camposano: The product that Ecuador exports, fresh tilapia fillet, was replaced by frozen fillets coming from Asian countries, such as the case of pangasius. This is part of the problem that the U.S. has in terms of labeling, the average consumer knows he’s buying a fish but he doesn’t know what type really, so if you’re looking at a frozen fillet that has less quality and that costs less, there is really no way to differentiate it from another fish by looking at the label.

So basically, our tilapia was replaced by a product that was a lot cheaper, but it was not equivalent.

Today the consumption of tilapia in Ecuador is very high when compared to other fish, so the market pivoted to attend to the domestic market, and now you see a high representation of the fish in supermarkets and restaurants. Now the consumption is local, with the positioning of the product as a healthy food, etc.

SeafoodSource: But the domestic market was able to take on all that was lost in exports?

Camposano: The domestic market is still small, so there was a definite contraction. The industry had various actors, farmers, processors, exporters. But today there is only one producer that survived and is serving the local industry, which is Santa Priscila, which is also one of the largest shrimp producers today.

SeafoodSource: Are there plans to reactivate the tilapia sector?

Camposano: There were two things that happened. One was that we faced competition with different products at a much lower price, and we couldn’t compete. We offered a high-quality fresh fillet, which requires a completely different logistics than frozen. We were competing with lower-quality frozen product and with that you’ll never be able to match the price.

The other thing was that the tilapia industry was born as an alternative to shrimp production, when the shrimp industry was affected by the white spot syndrome. That’s why it started towards the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s.

But the substitution of tilapia in the U.S. coincided with the rebirth of the shrimp sector in the mid- 2000s, and spaces dedicated to tilapia production were reconditioned to produce shrimp again.

SeafoodSource: Considering the crisis you had with white spot syndrome in shrimp, are you looking to develop any other fishing sectors in order to diversify?

Camposano: Looking at the public policy, there is always interest in diversifying the offer in Ecuador. There is aquaculture production for domestic demand, in the east of the country it’s subsistence farming. It’s divided into two different markets, the commercial market, where you see shrimp and salmon farming and there are high investments, very competitive, high levels of productivity per hectare that increases each year because of the research and the resources invested in these products. On the other hand, there is the subsistence aquiculture, which works on small pieces of land, for own consumption or for local sales. This exists in Ecuador for trout and tilapia, but in order to replicate that to match the shrimp industry, I think we’d need several years to get there.

Today Ecuador represents 65 percent of the shrimp production in all the Americas and it’s difficult to compare that level of production and that success with the other products being produced in aquaculture. Yes, it’s of interest – to replicate what Ecuador has done in terms of shrimp would be a great success for the country but it would require a series of factors; you also have to consider the learning curve in new aquaculture production.

Ecuador’s shrimp industry has been around for 50 years, but in the last decade, it’s quintupled production and exports – multiplied five times over. Production of shrimp in June of 2011 was 26 million pounds [11,793 MT] a month. Today, that’s 125 million pounds [56,700 MT] per month. What we did back then in half a year, today we do it in a month. And there’s potential to continue growing, so the investments done [in shrimp production] can make improvements that would go much further than if you were to invest in another product.

SeafoodSource: Even so, you don’t want to put all your eggs in one basket…

Camposano: No doubt. In terms of aquaculture, Ecuador has a lot to advance in public policy compared to what was taught say, ten years ago when we had a lot of technical errors. But in overall aquaculture terms, the actual products developed are still limited, shrimp and salmon, you have to make sure the climatic conditions are right in order to then move on to another species. In the case of tilapia, first it was adapting to an introduced species.

You also have to consider the market. I consume the product because I know of the production criteria - you can control the farming systems, the sustainability of the resource - but you have to think that the final consumer would have to stop purchasing what he normally does and change over to a high-quality fillet. How receptive is the seafood market for these aquaculture products that aren´t going to be the cheapest?

One of today’s biggest flaws in the North American market, is that the labeling doesn’t allow you to arrive with a new product and differentiate yourself immediately. You get placed on the supermarket shelf as “fish.” Most of the time the consumer doesn’t know what he’s buying. He can go to the restaurant and see the different types of fish, but he usually doesn’t say, “I want cod, sole or mahi.”

So it’s trying to get into a market that has commoditized the consumption of seafood. It’s even difficult for us to do it with shrimp. We have struggled to differentiate Ecuador with best practices, but the market sees a label that says “shrimp” and then in the fine print it says it’s coming from India, Ecuador, or Thailand. There’s not much interest in differentiating.

So the big debate is what the next salmon or the next shrimp will be for the aquaculture industry. Those are the two commercial champions so far. There are lots of technical reasons as to why others have not been introduced, but you also have to consider the commercial reasons. I hope we are able to differentiate and discover another product that moves USD 4 billion [EUR 3.4 billion].

Image courtesy of Ecuador's Camara Nacional de Acuacultura

Share