Chile rejects proposed constitution, granting salmon sector a reprieve

Chilean citizens overwhelmingly voted to reject a proposed new constitution on Sunday, 4 September, in a move that prevents further headaches for the country’s USD 5.2 billion (EUR 5.2 billion) salmon-farming sector.

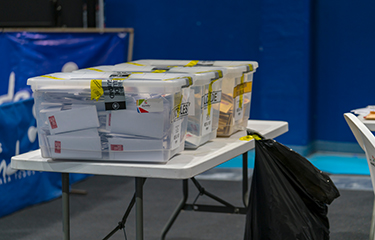

According to Servel, Chile’s elections department, 4.86 million people voted to approve the proposed constitution, while 7.88 million rejected it, meaning the measure failed 61.9 percent to 38.1 percent.

The initiative to rewrite the nation's constitution was brought about by a national referendum in October 2020, in which 78 percent of Chilean citizens voted in favor of electing a group to draft a new constitutions. Chile’s democratically elected constitutional convention worked for a year to write the new national charter.

“Today the people of Chile have spoken and they have done so loudly and clearly,” President Gabriel Boric said on 4 September. “They have delivered two messages to us. The first is that they love and value their democracy and trust it to overcome differences and move forward. The second message from the Chilean people is that they were not satisfied with the proposed constitution that the convention presented to Chile, and therefore they have decided to clearly reject it at the polls.”

Boric vowed to would work with Chile's congress and civil society groups to determine what next steps the country will take to reform the country's government. Chile's current constitution was enacted in 1980 under the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship, and a new constitution was proposed in October 2019 as a way to placate the social unrest and violence that has rocked Chile for years, affecting key parts of the economy, including salmon production and exports.

In response to the results of the vote, salmon industry executives called for a unified effort to find a political path to social harmony.

“The result of the plebiscite was overwhelming. Chile is seeking to begin a period of national unity to create, through dialogue, the conditions to jointly build a path of sustainable economic and social progress for our country,” Chilean Salmon Council Executive Director Joanna Davidovich told SeafoodSource. “The challenge now is to achieve a broad cross-cutting agreement that helps reduce uncertainty, build confidence, and move forward in a modern framework with a view to the future that drives investment, growth, and employment. We hope that this process is carried out in conjunction with the private sector, to see what the productive sectors require and to promote changes in a responsible manner to advance in a better country in which to live.”

Trade association SalmonChile called for a similar approach, highlighting “the participation and the republican spirit” that marked the day of the plebiscite.

“As an association, we believe that what is important now is to quickly seek a broad agreement to define the steps to follow and promote instances that allow progress in a new constitution,” it said in a statement sent to SeafoodSource. “We are available to work collaboratively to establish a dialogue that includes our productive sector, the 7,000 SMEs that are part of its productive chain, our 70,000 workers, and all the communities with which we interact daily.”

SalmonChile CEO Arturo Clément previously criticized some of the clauses in the proposed constitution, arguing it contained ambiguities that were not good for the salmon-farming sector's development. The constitutional working document contained language that could have forced salmon farms to be removed from marine protected areas, which could have impacted as much as 30 percent of Chile's farmed salmon production, according to industry calculations. Some of those protected areas are located in the ancestral territories of Indigenous peoples, who would have been granted new rights in managing their own lands and communities under the proposed new constitution.

“This is a very sensitive issue. Today the industry operates in national reserves in areas suitable for aquaculture and that were granted by the state for the industry to develop,” he said. “We are there because they gave us those concessions before they were a park, and we agree that a solution has to be sought. The issue is more complex in reserves that are multipurpose areas, where there are conservation and productive activities.”

Exactly how Indigenous rights might be defined so as to determine the continuity of salmon farming in protected areas was insufficiently covered in the proposed document, which could lead to future instability, Clément said.

“It is unclear what the Indigenous peoples’ attributions will be or what the relationship will be between those of us who operate in the area that supposedly corresponds to those territories,” Clément said.

Clément lauded the draft’s increased environmental focus but called for a pragmatic approach to reforming the industry.

“We see a worrying bias with an extremely environmentalist focus,” he said. “We believe that there has to be an adequate balance and there has to be much greater environmental care than in the past, but we also have to reconcile that care with economic development.”

The rejected constitution also contained langauge concerning animal rights, but did not specify which species the reforms would cover.

“The lack of definition opens the door for the concept to be expanded, because probably, in the original document, only pets were considered,” Álvaro Villanueva, partner at law firm Alemparte y Villanueva, an expert in public law, said previously during a presentation organized by the Unions of Salmon Workers. “If the convention’s proposal is approved, environmental organizations could in the future ask to regulate the ‘quality of life’ of salmon, which could be considered sentient beings. I am not aware of any international studies on how salmon feel, but regulating this matter could result in the closure of facilities, with organizations saying that salmon are not in their natural habitat, but rather locked up, and activity is restricted."

Apart from the constitutional process, Boric has previously said he hopes to replace the country’s existing fishing laws and strengthen Chile's environmental stewardship, particularly in protected areas, including a possible moratorium on the farmed salmon sector that would halt its expansion.

“What we are looking for are clear and long-term public policies because this is a long-term industry. As such, to the extent that there is little clarity, the salmon sector may face complexities in the future,” Clément said in response.

If the country continues to pursue the adoption of a new constitution, it must receive a majority of the popular vote, in addition to receiving approval from four-sevenths of Chile's congress.

Photo courtesy of Klopping/Shutterstock

Share